Responses to the Rachel Dolezal fracas, from newspaper articles to tweets to clever facebook statuses, were being produced at an unimaginable, yet recognisably competitive speed. Bombarded by article after article in my newsfeed, it was made increasingly clear to me why I had been gradually frequenting my facebook newsfeed less and less over the last year. I felt the old compulsion and pressure to read them all, but certainly I couldn’t; what with two children (one newborn), d(r)eadlines at work, and just genuine tiredness— I decided after all to share the articles to my wall, solely for the purpose of (and convincing myself that I would be) returning to them. Perhaps it is this velocity of retort and analysis, this speed of light enlightenment that made so many of these responses—-when I eventually sat to read them —- sit uneasily with me. The Rachel Dolezal issue is, of course, only the newest in a series of events that take place in America annually in which that nation’s injustice and disrespect for African-Americans shows its ugly face. This is something of course, Caribbean people are usually genuinely outraged about but also appeased by, smugly deluding themselves into thinking that this is not here…there is not here….sunshine…..margaritas…mangoes etc. etc. etc, no no no, not here. But this particular issue was a little bit freakier than it usually gets, a little more bewildering. And as difficult as it seemed for charlatans, social-media bandwagonists and others to join the mob with a trite expression of outrage, many still joined in with their frowning hashtags and self-consciously cunning phrases. So here we have a lady of Caucasian parentage deciding that she wanted to confront the woes of this disenfranchised group of Americans. A woman who sympathized or somehow identified with the struggles of a marginalized group and wanted to move toward action. To complete or satisfy this sympathy or identification, or whatever inner need or desire urged her toward her decision, Rachel Dolezal decided that she needed to be black, phenotypically and, I guess, otherwise. (although the story could possibly be a lot less romantic that we are making it) My first thought was that this should be a field day for the liberals and intellectual relativists whose criteria for membership is just as simple as that which permits entry into the outrage bandwagon. And on both ends— the righteous indignation of the so-called essentialists and the languid, hippie-like daze of the liberals—- there seemed to be misplaced sentiment, platitudes, clichés, bromides, secondary rationalisations….you get the point.

I’ll leave you to guess which camp the following defenses or attacks emerged from:

1) Black people are obsessed with weave, straighten their hair, wear coloured contact lenses that simulate grey or blue eyes typical of white people. So why can’t this white woman be black.

2) If Bruce Jenner can turn himself into a woman or be transgender, then why are people railing against poor Rachel. (Who at some point was designated as ‘transracial’)

3) The problem is not that she changed her race but that she lied! (Lying bad!; honesty is the best policy and other girl/boy scout lingo )

4) Not only did she lie, but she changed her race so that she could be employed with the NAACP. In effect, robbing black people from being at the helm of an organization which was started by, and headed through out its existence largely by Jews or whites.

5) Oh look see. That one drop rule has come to bite them niggas in the rear end!

6) This girl got issues. Point blank. Period.

7.) Oh the irony. Black people giving this white girl all this attention.

Some of these points are simply not worth arguing. At best, they deserve to be given a time out in a corner with very colourful charts reproving bad behavior in colours with names like ‘bubble yum pink or ‘piggy pink’ or a perhaps a mob of frowning emoticons. My personal favourite of them all is actually 6) and although it seemed perfect in its bluntness to the extent that it felt like sacrilege to add to it, it is, in all honesty, my own starting point. Partially paralysed as I usually am before a keyboard, anticipating the labyrinth of the intellectual relativists, I thought that I needed to dodge them by avoiding talking about race head on. It’s also possible that I was commiserating with poor Rachel, because it seemed that she was being bombarded within a matter of days with so much just as I was becoming aware of how much I am bombarded and made to feel guilty by the deluge of over- information that I am not able to consume. Right word: consume. So my stance, my public-social media stance (i.e. facebook) was ‘to me this seems to be a personal issue.’ And like all self-delusion, you say it often in the hope that you will eventually imbibe your own lies. And then to make things worse, Teju Cole comes along, posting a status that is in accord with my own lies to myself! Damn you Teju! He says: “I’m not interested in setting rules for anyone else. And there are undoubtedly people who merit sharp public rebuke. But I think our social networks facilitate mob-like behavior. I think they too easily absolve us of our own foolishness and oppressiveness, and they can cause a too extreme rebuke of the kind that is all out of proportion to the foolishness they are correcting. It’s easy to forget there’s a human being, even if it’s a very foolish one, at the receiving end of the ire of millions of people.”

It’s a sentiment I still bow my head reverently at and with closed eyes in agreement with, but there were other issues for me of course, just as there were for Rachel. Things are just never so simple within oneself as they may seem to be without. Before I could even deal with Dolezal, I was brought back to certain white commentators, sometimes friends or associates whom I found it difficult to place into any easy category in my head. This is my Caribbeanness talking, for there was no easy dismissal into categories such as Republicans, White Supremacists or any of that. Although more than one of the persons I am thinking of were from the United States, the Caribbean was not the milieu where such terms were supposed to have immediate meaning, there was little epistemological room for such terms. The person or ‘type’ I am thinking of is the white persona who champions black rights, champions it so aggressively, wielding a whip of accusation at their fellow white brothers, at the slightest peep. The type that casts himself as the black sheep in his white community, who dramatizes his scape-goat status, persecuted or ostracized by his own race because he has chosen the path of the just, dying, as it were, for the sins committed against us, black people. Not for the sinners but for those sinned against.

My encounter with this type was particularly troubling, because I found it so difficult not so much to place him, but to place my own discomfort with what he saw as his ‘identification’ and even erudition when it came to not just black struggle but all things black, from Alabama to Rihanna. The other type is not as impudent, but enacts a kind of reclined, arm-chair anthrolopologist kind of posture. The know-it-all who knows all-too-well how all systems work and how all systems could be fixed. A white blackness-specialist. I told myself that my confusion concerning my own resolute feelings of distrust toward these types was something I had to deal with to properly understand my own relationship to the catalogue of atrocities against black people that paint my newsfeed throughout the year with blood.

A friend from high school, after the Baltimore demonstrations or riots, decided that it was a perfect opportunity to saddle and superciliously condemn the rioting. It was an opportunity for sarcasm, for revealing irony, for satirizing. He ‘opines’: “Damn, Baltimore needs to import some of those Korean L.A. riot veterans to show how to handle these ;peaceful protesters’. Rioting and looting surely gets your point across in a positive way.”

A brief diversion:

I recently picked up V.S. Naipaul’s authorized biography The World is What It Is, by Patrick French, and am currently on a chapter concerning V.S. Naipaul’s burgeoning romance with Patricia Hale who would later become his (first) wife. Naipaul at the time is barely a writer. He is struggling financially, suffering psychologically and is dependent on Patricia who is miles away from him and prohibited from seeing him by an overbearing and racist father. But then a boon:

“I hear that the BBC man, in a review of the work he has broadcast speaks of ‘V.S. Naipaul’s corrosive satire.’ Don’t you want me to keep on being a corrosive satirist? It is my nature. If I write otherwise I shall keep on being a corrosive satirist? It is my nature. If I write otherwise I shall cry as I write, like Dickens. I can’t write about sadness sadly. It would kill me…. Oh darling, I love you from the bottom of my corrosively satirical heart. Your own Vidia.”

Pat’s astute opinion of Vidia’s stories however was that they “had humanity, but not in the full sense.”

***

And there I found an explanation for my conflicted relationship with satire and irony, my suspicions of these devices as the basis for a style, especially coming from someone as dangerously talented as Naipaul. One has the same conflicted feelings toward its diametrical opposite: the maudlin lyric. Admittedly, we know better what to do with tragedy than we do with comedy which always seems on the verge of upsetting things and putting someone in trouble. Neither of them however give us a full sense of their subject’s humanity. There are of course situations where these pieces of our humanity are apposite and fair, but irony, parody, sarcasm and satire always struck me as fair game when they were leveled at powerful figures; weapons of the disenfranchised, the marginalized, the oppressed. I see them as devices used to inflate the ego of the oppressed person or to embolden him, to grand-charge, to rebel, an attempt to undermine the seemingly incontestable authority of the powerful. Used by the powerful toward the oppressed, or even the oppressed toward the oppressed, it always had the effect of rankling me somehow, always seems obscene. (I hear the relativists breathing down my neck here, demanding nuance in a series of disorienting questions — who exactly are the oppressed?; aren’t the powerful also somewhat oppressed?—- but I’m okay with breathing and necks and even nuance). For me, the deployment of either of these extremes to the complete exclusion of the other are less expressions of our humanity than they are strategies for achieving a milieu in which more honest confessions of our humanity may have truer meaning. Like literary affirmative action.

***

But what my encounter with my smug and sarcastic white friend revealed to me, (after I was unraveled and drawn out) was how easy it was for him to both enter and leave the discussion, the situation, the maelstrom. How he could stride in and out like a superhero into the fire saving no one. Not even himself.

Another thing that became apparent to me is also how unburdened he was by a clamour of voices from his own race pulling him back, feeling threatened by his sarcasm, that it may be bordering on some impropriety or on something incendiary, making them look bad. Not that this doesn’t exist, but not with the aggressiveness and desperation with which it exists in the black community. This fear however is at the heart of the black, public intellectual. It is a fear of being gobbled back up into a blackness that will not distinguish him on the basis of his merit, his accomplishment within the systems of achievement as they stand. This is, of course the same point of origin from which successful black persons argue that “if I could make it through “the system”, why can’t they?! I’ll tell you why, it’s because they are lazy, they are filled with self-contempt, and self-pity.” The fear of being pulled into that brimming black (w)hole is one of the deepest fears of the black intellectual and betrays the tenuousness of his own position of putative success and even, mastery. From this fear arises symbolic acts of disavowal in which the intellectual distances himself from talking about ‘race’, dismisses talking about race as a crudity, an attempt to ‘gate-keep’, to police. S/he recedes into a position that is teeming with questions whose very existence protect him/her from having to take a position, because the answer to all these questions is always that there is no true position to take. Everyone is, more or less, equally right or at least has a right to say whatever. S/he is the type who hardly “objects” but is usually “wary” or “uncomfortable” or “scandalized”, or is “distancing him/herself”. If they are to say anything definite, they appropriate words and terms that those on the other side of the argument have used to defuse the situation. Interestingly enough, they are accusations whose terminology reflects the apparatus of the powerful ironically being leveled at the bare-handed black-footed disgruntled persons at the margin: “policed” “gatekeeping” “identity-patrol”. It would be remiss of me not to remark that there is such a position, when more sincere and less self-preserving, which results in black persons being critical and rigorously examining their own positions, by taking each other to task. Caribbean literature is rife with examples of these. And, it is common knowledge that the “essentialism” that the intellectual relativists are so scandalized by and ashamed/scared to be associated with, is the first weapon wielded against a group that is to be persecuted, but also the source of strength for the marginalized to stake a claim for freedom, respect, humanity. It is therefore both myth and history, as Benitez-Rojo would have it. And if it is a myth, it is a myth upon which some of the greatest efforts in history by an oppressed people to ameliorate their situation of dehumanization was built.

This brings me back to the last part of my friend’s seemingly pragmatic, though sarcastic admonition: “Rioting and looting surely gets your point across in a positive way.” And it is this that ensnares the black public intellectual. He is free to express divergent views that seem to rail against the status quo, but his way of doing so are predetermined by that same status quo. It traps him in a series of absolutes that is so reflective of the static objectivity and ontology that governs being and knowledge in the West: Violence is always wrong. Violence is never an option. Lying is wrong. Always. There are always more peaceful ways. Etc etc. So the intellectual comes off again feeling his superiority, for not only is he engaging in radical acts of disobedience and defiance in respect to the status quo, but he is doing so in a more practical and useful way than that mob advancing to claim him with sticky tentacles like the sargassum seaweed now blood-staining Caribbean seas. It is through experiencing and observing vigilantly the proliferation of this kind of intellectual, that I become more and more convinced of what persons like Earl Lovelace, Rawle Gibbons and several others of my own personal pantheon of luminaries have been saying. Or perhaps even the simple advice given by my mother that I willfully misinterpret here: “It’s not what you say, but how you say it.” Rawle would say “Until the Caribbean resolves Haiti, it will not go anywhere”. Haiti that is known for Voudou which has been condemned less for who the Gods they worshiped were (which of course it is difficult to say) than—- as the several American films on Voudou have depicted— how they chose to worship, summon or acknowledge those Gods. I am thinking as well of Earl Lovelace, as he observes in his essay ‘Reclaiming Rebellion’ that: “The drummers, calypsonians, pan men and flag women would not be seen as decent people. Decent folk was a term then in use, not so much to distinguish one class from the other but to separate people of the same economic class. It was not always about having money or property, but about aspiration not to be lumped in with those who had been deemed delinquent for engaging in religion and culture that had an African origin—- the religion and culture emanating from the poor class: the jamettes, the rebellious, the loud and unruly or, as the famous calypsonian The Mighty Sparrow calls them, ‘outcast’.” And Erna Brodber who observes in her foreword to the book Obeah and Other Powers: “They were living with burning candles….keeping their heads covered, leaving plates of food in their yards for the ancestors, but they still did not know if they were connected with the feared obeah man down the road, formerly the butt of jokes in their friendship networks.” I suspect this may be why I bristled at a certain Caribbean writer’s recent blog adding its voice to the mob pillorying Sheree Mack, a poet who had appropriated the work, without acknowledgement, of several British writers, earning her a reputation as a serial plagiarist. It was not so much that I felt that Kei Miller was wrong about Mack, (though the issue of cultural appropriation was problematic for me) but that the blog seemed to remind me too much of those symbolic acts of distancing that I find troubling, paradoxically emerging from a similar place as those “decent” and “positive” ways of being subversive, so different from ‘the rabble.’

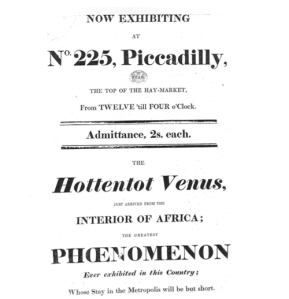

But even while black intellectuals pledge allegiance first and foremost to ‘nuance’, ‘intellectualism’ and ‘objectivity’, their entry into the circles dominated by the white establishment is nowhere near the ease with which my flippant facebook friend conveniently enters discourse and condemns, no where near the privilege enjoyed by the most unintellectual and foolish white commentator. (If you don’t believe me, spend some time with a particular American news station named after an animal normally characterized as being ‘sly.’) And this is where I recognised how this truly personal issue (psychological, physical, emotional) also finds its way into the public domain, and worthy of public outrage. Rachel finds herself being lumped now, by indignant black people, with an impossibly long tradition of white irruption into black bodies; black-space (even though her entry was less an irruption than a “sneaking-in”). Largely this space has been immaterial, it has been the space of creativity, of imagination, or innovation. It is the space of obeah, of jazz, literature, capoeira, love, sex etc. This alien entry involves the brazen and flippant appropriation of cultural products, of intellectual property. Some of the pirates have stolen many precious truths and left a trail of lies in their wake. Perhaps it is that constant threat of white (or sometimes “Afro-saxon” to use Lloyd Best’s still apposite term) irruption that helped Erna Brodber conceptualise her Blackspace, an event? — no: a space, physical and discursive, that she creates every year for black persons worldwide to come to discuss, argue, interrogate their issues in soft and loud peace, without being circumscribed by that sense of entitlement that feels the need to intervene, to arbitrate, to correct, to reprove, to domesticate. Without the privileged satirists and ironists tossing pieces of our humanity at us. This is Rachel’s transgression perhaps. Both hers and not hers. Something like original sin, but one that has never ceased repeating itself and even evolving in order to ensure its survival and its place at the centre of things. And her situation is worsened by another more beautiful type of irony: a group of white protesters, proclaiming that #Blacklivesmatter in the wake of the Emmanuel AME Massacre in Charleston, in their own skin, not in blackface.

***

Talking about race in the Caribbean is a much more difficult thing to do than doing so in the United States. It is no wonder then that American atrocities also operate as a kind of cathartic space for black-Caribbeans. The subtle censorship of anything verging on racetalk in the region by labeling it as crude, unintellectual or even impolite is perhaps one of the longest steps backward the region has taken, perpetrated many times by its artists themselves who have an anxiety, as old as the Caribbean, about being lumped with the mass of black persons. So as much as Caribbean intellectuals have come out to condemn or comment somehow on the racial Dolezal issue, a white Caribbean writer could write the following lines in her book, without so much as a peep from anyone within these circles: “Georgia stretches her arm out of the window. The goats carry on eating as if they are not there. They are white and scrawny. It is something he has noticed here: cattle and goats are often malnourished, their stomachs distended and bloated. Like Africa.” This from a book that received rave reviews in the region.

Recently at a book fair in St. Martin, myself and another writer based in the region, after a day of panels and discussions found a bit of time to lime at the hotel, and over a couple rum and cokes, we were reflecting on how important these informal spaces were, these spaces usually seen as outside the realm of deceny. I was telling her about a small observation I had made on facebook where a friend of mine bemoaned bitterly the destruction of Greyfriar’s Church in Post of Spain, but that same friend was apologetic in morning the burning down of Smoky and Bunty a legendary liming spot in Trinidad within which so many memories were made, to a certain degree, irretrievable by the fire. It struck me that it was in these in-formal places, in these places prone to mis-behaviour or acting outside of Power’s definitions that governed and regulated behaviour, where we are most ourselves, are able to talk freely. Of course there is risk involve, there may be falling out, vehement disagreement even fights. But it was not a place we have traditionally been afraid of, it has always been a risk we seemed willing to take because there was the greater reward of self-discovery.