One of the CDs I have playing over and over in my car, is a live recording of Linton Kwesi Johnson backed by the Dennis Bovell Band, in Paris. I am sure this recording was not Linton’s first or perhaps even tenth trip to France to perform. Prior to listening to this CD, I had read Caryl Phillips’ essay, in his collection New World Order, entitled “Linton Kwesi Johnson: Prophet in Another Land”. The essay was written in 1998. Perhaps with a certain degree of naivete, I kept wondering what the French audience found in Linton’s lyrics that spoke to them so clearly and sharply that they, as activist William Tanifeani says to Phillips (who wanted to know as well),” You see, Linton is, along with Bob Marley, the most important of the reggae artists that have come to France. People listen very carefully to his lyrics. When he sings “Inglan is a Bitch” or “Sonny’s Lettah” French people know all the words.” Still, to some degree this does not explain his importance, and the comparison to Bob Marley makes it worse. Not that Bob’s lyrics are not taken seriously, but to some degree in the tourist-infested Caribbean, we have come to understand how Bob’s music has been appropriated in an almost blasphemous fashion, to lure tourists to a paradisical Caribbean of people black, faceless, inexplicably happy and vacuous as the men on the No Problem Jamaica T-shirts. Tanifeani goes to explain that “Perhaps the time is right for us here,”he suggests. “Back in the Seventies when you were having a lot of trouble with the emergence of your second generation of black people, Linton was saying things that you needed to hear. But now? Well, maybe it is us who need to hear these things.” Phillips who is sitting with Tanifeani at a restaurant is soon joined by another activist who offers him photographs of Linton speaking to French boys and girls of North African origin in an area just outside Paris.

Tanifeani’s sentiments are important here. But what about the several business interests and persons who bring Linton in? Certainly part of it is because the great man has attained, to use an odd new phrase, “rock star status”. But music has that kind of power anyhow, even though there is not immediate connection to the lyrics, even though its full effect is staggered over a prolonged period of listening. Some may never connect. Some, perhaps those whose interests and privilege Linton’s words threaten, may find solace in believing that Linton is just that—- a rock star and nothing more.

I first met Linton in person at the Bocas Lit Fest in Trinidad. Bocas has become one of the premier lit fests in the Caribbean, alongside Calabash, and in terms of its organisation and offerings can compare, I am sure, with other international literary festivals. The second time I met him, was recently in early September, at a literary festival in Amsterdam, called the Read My World festival. Linton was brought in to do the keynote speech on the opening night of the festival. It was speech was a touching speech on his own life in England, the growth of his political consciousness, and how he came to see poetry and reggae music as a suitable vehicle for creating the kind of change and awareness he wanted to generate in the society in which he lived. Listening to him, there came to me the realization that always comes to me at some point with one of those luminaries of West Indian literature: that it was no longer those fiery years in the middle of which I encountered them in books or old articles. I mean the man’s poetry is in no way effete in his delivery, but there is the obvious realization that the place and time at which you fell in love with them, is a time past, a place that existed in the way it did, only in these poems and other recordings. And the men who sing or recite about those times may not produce that precious fiery as hot as it was before. Their convictions are still there but exist in a more elusive, more internal and reticent form.

But what was Linton doing there? Why was his life so important to this festival? They could have brought him in, hinge the festival on his “rock-star status”, have him do a few numbers, sell his CDs and send him home with a cheque fat enough both as remuneration and as an investment in future endeavours in which they would require if not him, then his status, his influence and appeal. The life of the man is in the songs, the poems, in more marketable form. What were the other writers who were there, doing there? The roster of Caribbean writers present were new and emerging writers, some barely known in the region, most hardly known internationally. And all of us, doubly-removed from the linguistic setting we were in: none of us spoke or for that matter, understood much Dutch, if any.

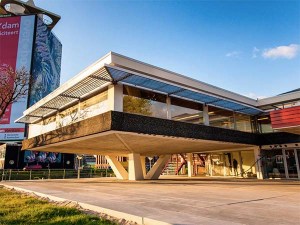

True I have been to relatively few literary festivals. My own book has only been out for a few months—- my debut collection of poems. So certainly I was not invited on the basis of any supposed “rock-star status”. But it struck me that every literary festival I have been to, has always had a sort of quorum of rock-star writers. Part of this is what makes a lit fest, and understandably, what draws an audience. I remember the feeling of seeing writers I had read like George Lamming, Earl Lovelace, or even younger writers that excited me like Tanya Shirley or writers I hadn’t read much from like Marlon James walking into the Old Fire Station building in Port-of-Spain where many of the Bocas activities were held. Such an experience is always compelling and perhaps foists upon you your own negligence of not having read their works or not having read it properly. And maybe there were Dutch rockstars there as part of the festival, but the festival was focused on us, on the Caribbean. The previous year had been focused on the Middle East. It was, oddly enough, our festival, at the Tolhuistuin in North Amsterdam.

It wasn’t until it was time to leave, until we were in a room choked with cigarette and marijuana smoke and books and laughter that it became absolutely clear to me why I was there, why we were there. Each day came with its own contribution to that clarity, like the charming East Indian woman with tousled hair who brought us breakfast each morning in a basket. And the night when Linton came in and delivered his keynote brought me several steps ahead in that realization. Linton, in a sense represented, the actualisation of what many of the artists there seemed to be incipiently engaged in. Ruel Johnson, and his activism in Guyana. The younger Sara Bharrat and her brave speech, “Break Your Silence” delivered at the award ceremony of the Inaugural Walter Rodney Foundation Creative Writing Competition. Sheldon Shepherd and his work outside or perhaps deep within the NoMaddz movement, the deeply serious Adrian Green from Barbados, and all the others. But why was I there? I had written a book about my family, revisting and trying to complicate stereotypes, reclaiming those I had rejected in my mind in earlier years with the popular epithets that always generously served self-contempt: sambo, country bookie and so on. I had written of people I hoped to one day be like, people whose works had changed my life: CLR James, Walter Rodney, my father, my mother. I had written about the submerged belief system in St. Lucia and most other Caribbean islands: Obeah, not in defense of it or championing it, but from my ethnographic work trying to render it for what it was— trying to deal with it less as a scholar or a Caribbean representative, and more as someone living in its midst. And there were, at the very end of the book, a few poems on living in a land dependent on tourism. More and more the question was, not why were we there, but why was I there?

A few days after we arrived, co-director of the festival, Matthijs Ponte had organised a tour of Amsterdam for us. It was a tour. Soon we realised it was a black heritage tour, and one of the other participants expressed his mild disapproval. Why not a simple tour of Amsterdam? Towards the end of the tour it became clear that little of what we had heard or seen on a regular Amsterdam tour would have brought us here, to the dark underbelly of that land, those brackish waters of Dutch maritime history, which the polder had now been thrust upon. As unassuming and modest as Matthijs was. It made sense. There was a clear vision, at least in his mind, of what we were here for.

The festivals I had been to compared to this one had a sort of hands-off approach. The expectation was that it would provide, like the Jazz festival at home, a fair share of big names, some other smaller names, some emerging names. The festival programmes would be decorated with popular topics for discussion, not necessarily drawn from a conscious sense of what needed to be discussed among Caribbean people, a rooted sense of what was most urgent—- especially what was most urgent to discuss about what is happening IN the Caribbean not what was merely de rigeur. A certain cynicism has set in around the talk of nation, in the Caribbean, around the importance of being or writing from the Caribbean, around saying things like what you see on Sara Bharrat’s blog: “I wil not be silent. I will not be silenced. I speak for my people, for my country until death, or without wax.” Or even the name of that blog: The Guyanese Experience. Ultimately in the festivals I have been to or read about there did not seem to be that sense of ‘movement’ that one suspected was very much part of the raison d’etre of the Read My World festival. And this need not be what all festivals are about.

The festival invited the Dutch public to hear Caribbean writers talk about what was happening in Caribbean nations, from writers or citizens who live in those nations. It invited its scholars to interact with the work of these writers, to listen, respond, to question. At risk of seeming corny: to read our world. And the intention it seemed was for this Dutch audience, not necessarily to take up some humanitarian cause or other in the Caribbean or to become Caribbean scholars or anthropologists, but to simultaneously become aware of what is happening in the world outside of Europe in very small corners of the World, as well as to become active in engaging their society with the same seriousness and rigour that Matthijs, Willemijn, Sharda Ganga and Ruel felt that we apparently had been doing. We did not come all the way to Amsterdam to defend our world, to engage in a kind of relativist politics or ‘writing back’ that ingratiated our culture or societies, to show our difference in quaint vignettes, we did not come to impute or incriminate the Dutch. Ironically, we were in a similar position as Jennifer, our tour guide of Surinamese parentage, walking the streets of Amsterdam, engaging her world before the Dutch people riding by on bikes. Except that her world really was Amsterdam and Dutch history, but a part of the history that, by design, Amsterdam was and still is protected from. Matthijs et al., with their own nuanced and variegated awareness of activism, were in many ways giving the Dutch public, through us, a dose of what they felt it needed. We were in a sense contributing to Dutch society, by speaking honestly from within our own countries.

It was only, on our last night in Amsterdam, gathered together in Matthijs’ apartment, cramped with books, the air live with cigarette smoke, wine skittering like lizards down our throats,the walls overtaken by shelves pleated with books—- it was only then that I became incipiently aware of what this festival was, what it was doing, what it had in fact done. Matthijs, who was more inconspicuous than others during the festival, could sometimes be seen sitting alone, staring pensively at whatever happened to be in front of him, his cigarette between his fingers. You could glimpse him sometimes sitting alone at the open-air restaurant at the Tolhuistuin, overlooking the river where the ferry brought people to and from central Amsterdam with the clutter and sizzle and silver of their bikes and scooters, smoke rising and curling from his cigarette like an undulating idea; a plan.